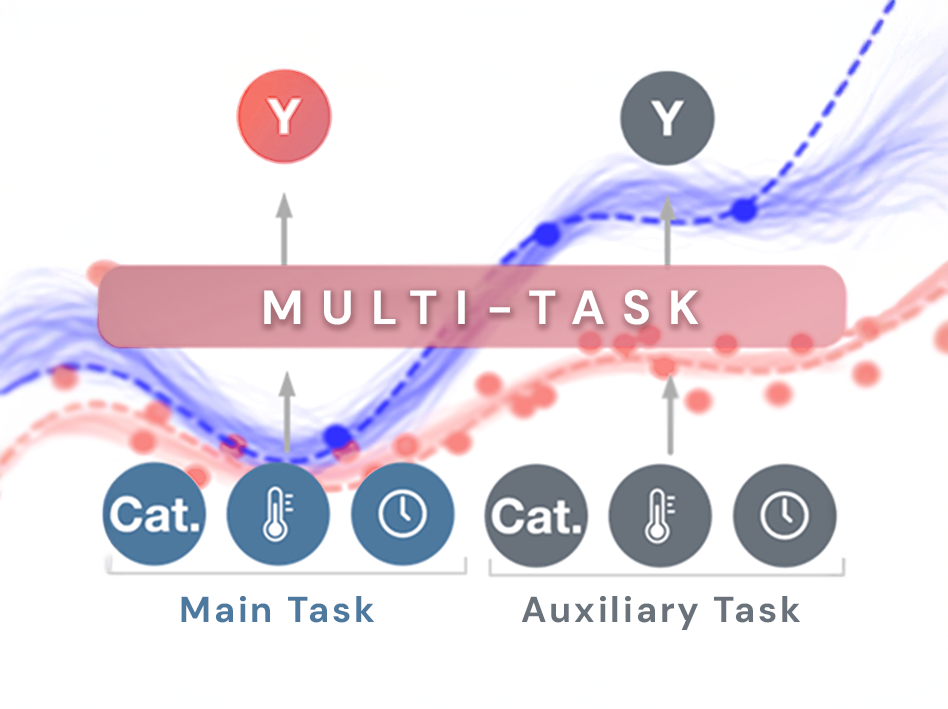

Reaction optimization has historically been done from a “cold-start”, using a trial-and-error approach uninformed by historical data. For reaction optimisation, we leveraged a method, known as multi-task Bayesian Optimization (MTBO), which learns from both historical reaction data as well as from new experiments. MTBO identifies optimal reaction conditions far faster than standard (single-task) Bayesian Optimization (STBO), which is not data-informed.

Bayesian Optimization (BO) offers a powerful and data-efficient way to navigate complex chemical reaction spaces. BO works by constructing a statistical model which is continually updated and improved with additional data. This model captures both the outcome (such as reaction yield) and the uncertainty across the design space.

At the start. when no data is available, uncertainty is high across the entire design space, so BO must balance exploration (learning the shape of the space) with exploitation (testing the most promising conditions).

A key insight is that this initial “map” of the reaction landscape doesn’t need to be constructed solely from the target reaction. BO can leverage information from related reactions to reduce early uncertainty and accelerate optimization. This principle underpins multi-task Bayesian Optimization (MTBO), allowing the model to learn from analogous chemical data to achieve faster, more efficient optimization.

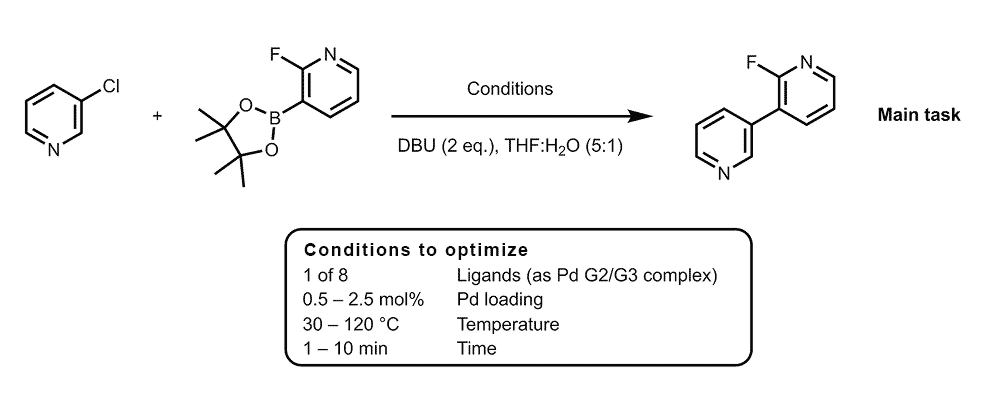

For the following Suzuki reaction, traditional methods to find the reaction optimum would require significant cost and time due to the size of the design space. Using Bayesian Optimization, without any prior data, could save some effort but would still require numerous experiments to map the reaction landscape before the optimum could be found.

Reaction scheme of the Suzuki reaction to be optimized.

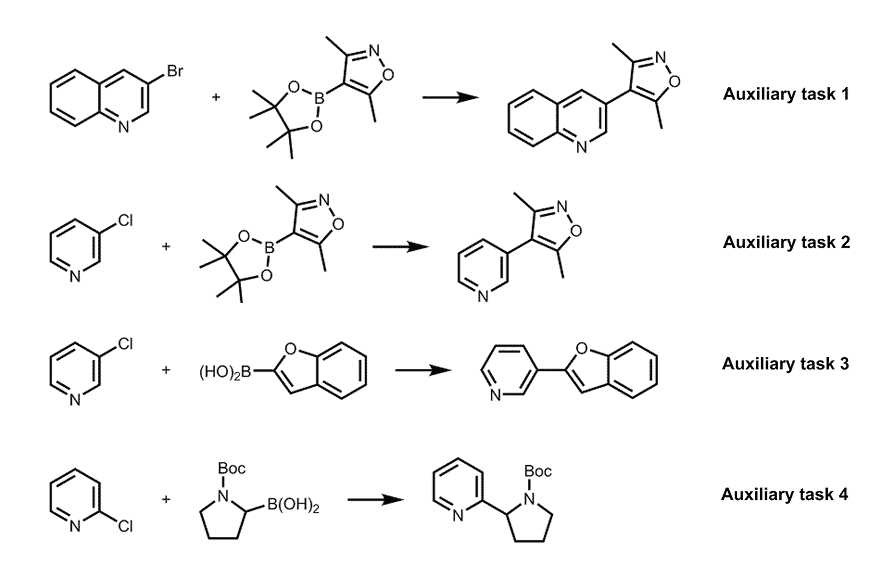

Reaction schemes of four Suzuki reactions used as auxiliary tasks, for prior data.

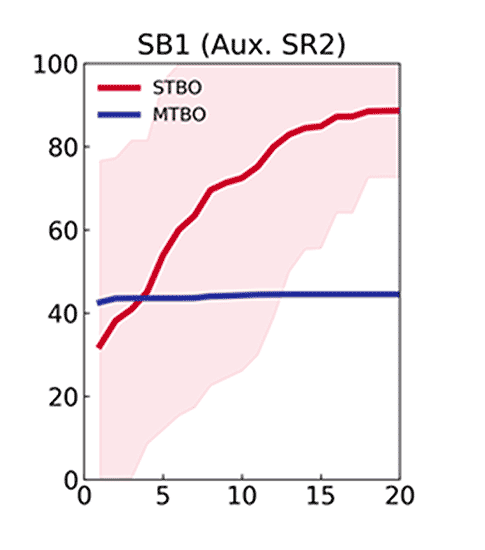

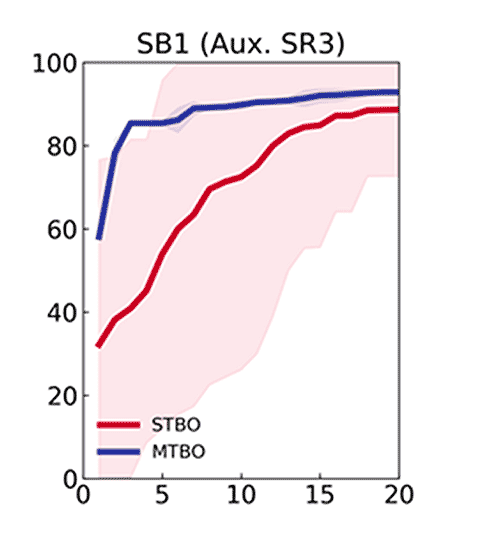

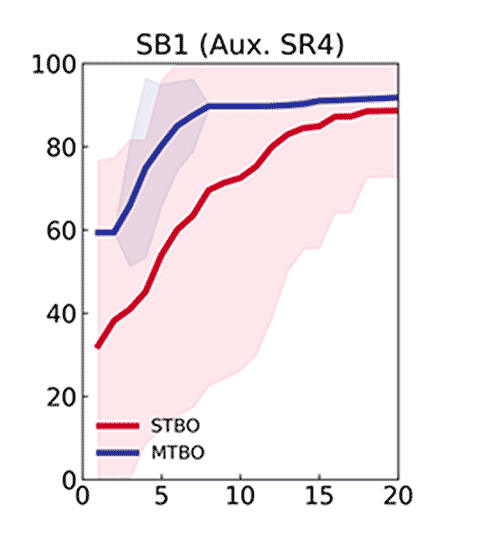

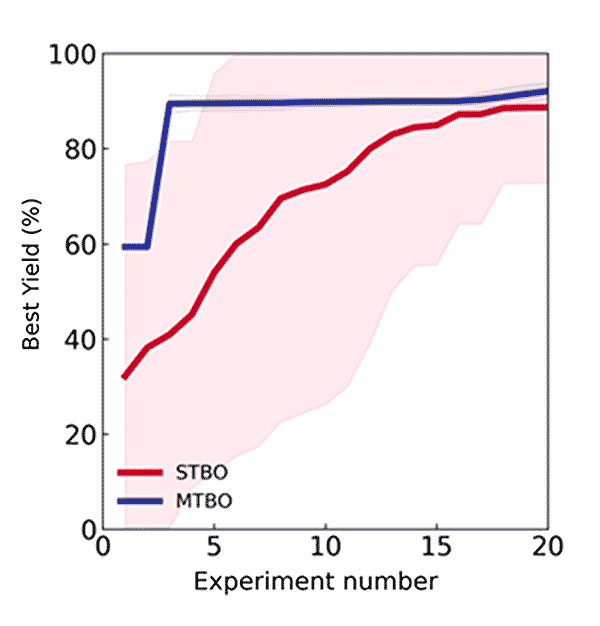

Using four different Suzuki reactions as auxiliary tasks with historical data, an MTBO model was trained and used to guide the optimization of the previously unseen reaction above. Optimisation of this reaction was fastest using the combination of these four auxiliary tasks and their historical data, compared to any single task alone.

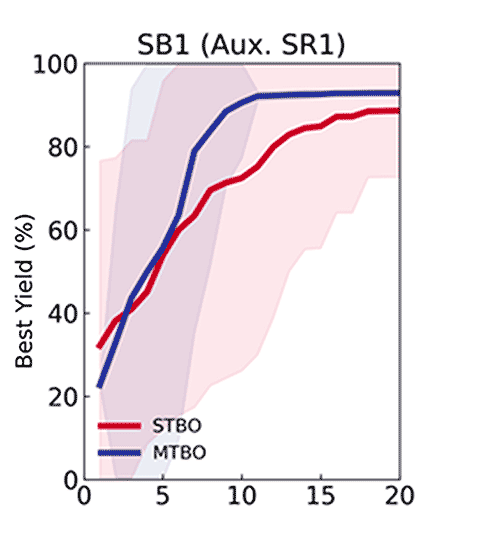

Optimization of the desired reaction when using each of the auxiliary tasks 1–4 to generate an MTBO model.

This indicated that, although MTBO performs well when the prior task resembles the main task, the greatest acceleration occurs when information from multiple auxiliary tasks are combined, even when some of those tasks are less similar to the target reaction. To further define the boundaries of MTBO and assess which reactions are suitable as auxiliary tasks, we explored flow chemistry as a platform for automating iterative optimization.

Optimization of the desired reaction when combining all of the auxiliary tasks 1 – 4 to generate an MTBO model.

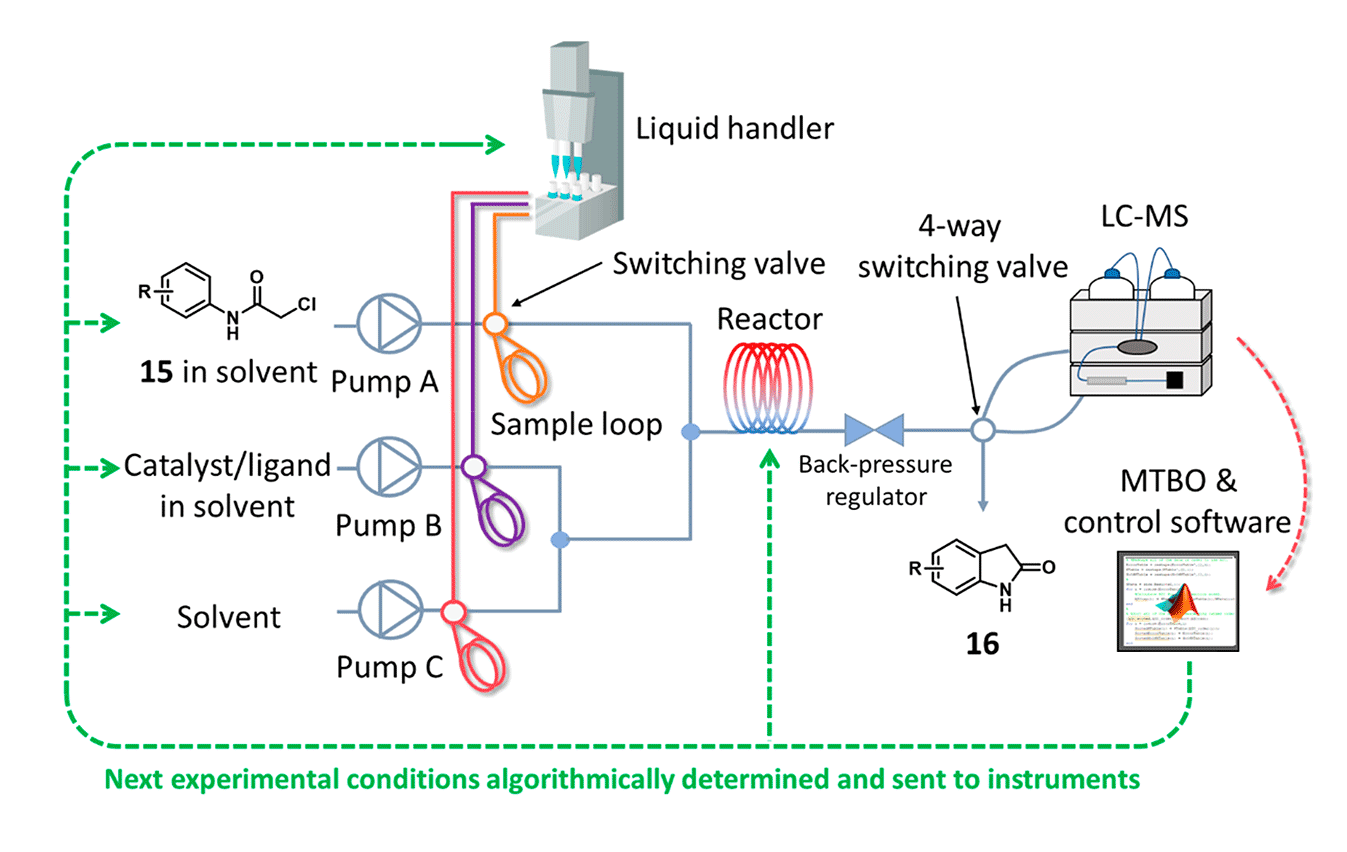

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup used for self-optimization in flow.

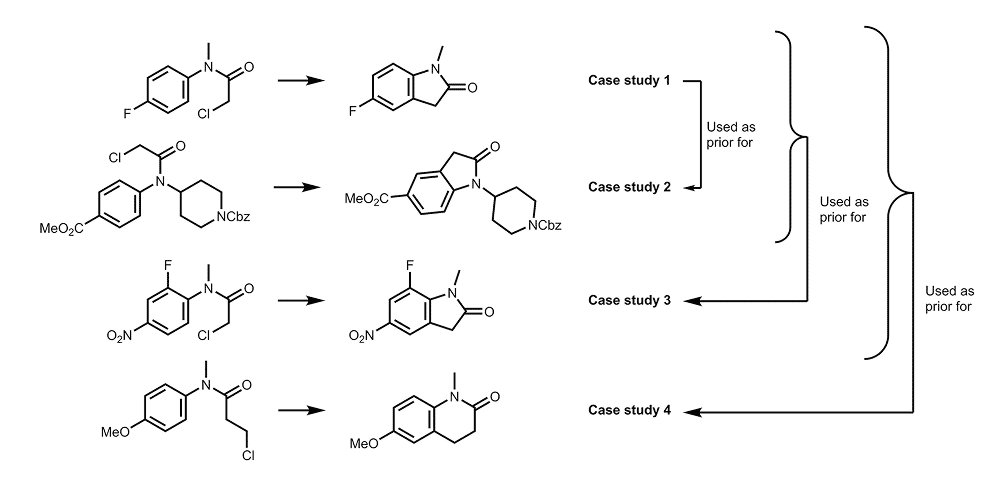

Reaction schemes of the four case studies investigated by self-optimization in flow.

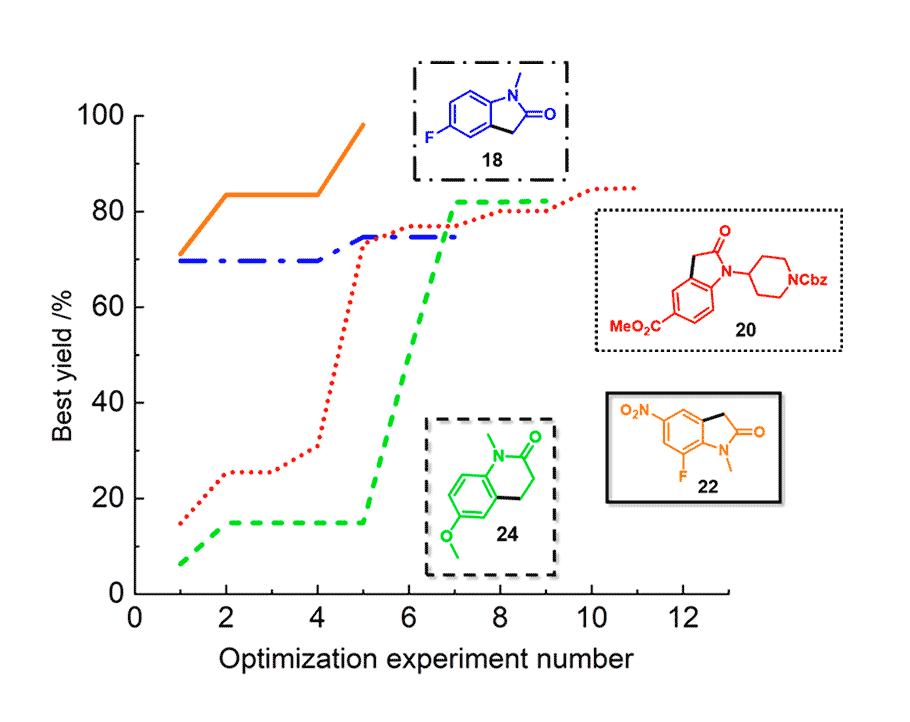

An algorithm-driven flow reactor was built to automate the study of palladium-catalyzed C–H activation reactions. After an initial set of 16 experiments (generated by Latin Hypercube sampling), the first reaction was optimised using STBO. The subsequent three reactions were then studied sequentially, each using data from the preceding experiments as priors for MTBO.

Optimization was fastest for case study 3, requiring only four experiments. This reflects the high structural and electronic similarity to one of its prior tasks, case study 1. In contrast, seven experiments were required to optimise case study 4, reflecting its differing ring size (6-membered vs 5-membered) and contrasting electronic character (electron-rich vs electron-deficient arene). Together, these studies demonstrate that MTBO benefits from training on prior reactions that are analogous in reactivity to the target reaction, though using MTBO for reactions in the same reaction class (e.g. Suzuki coupling) continues to vastly outperform data-uninformed alternatives.

Optimization performance of the four reactions studied.